Games:

echochrome

All games – even the daftest of pimp simulators or zombie mashers – stimulate cerebral activity, no matter what the Daily Mail would have its readers believe. And Echochrome is certainly not a game for Daily Mail readers: it’s way too clever for them. It’s a game for Guardian readers and, of course, SPOnG readers – that’s you!

So, this is how it works, clever clogs: you’ve got a little mannequin character that never stops walking unless you press [Triangle] to freeze the action and work out a solution to the stage. All this walking doesn’t get it very far by default, because it’s treading a path along the surfaces of impossible structures. That’s where you come in – you need to change your perspective of the structure, either by pushing an analogue stick or waving the SixAxis like, well, like a Wii Remote.

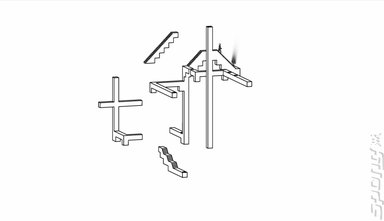

The control system couldn’t be simpler, but the level design is deliberately convoluted and all the better for it. I was stuck on the third level for half an hour. No shame in that, though, because Echochrome is more difficult than a cryptic Times crossword. One look at our Echochrome screenshots will tell you that it owes a huge debt to M.C. Escher and his mad geometry, but it’s not just something to leave running on your plasma display when it’s not being used... Echochrome is more than art: it’s a game. Ha!

There are a few nifty subtleties to the control setup, which seem to have been included just to smooth everything over. Pressing the [Square] button ‘snaps’ your current perspective to automatically link any linkable edges of structures; but only if you’ve already brought those edges reasonably close to an alignment. This is just a neat way of sidestepping the need for gentle-gentle perspective shifts; it doesn’t fully automate the path-finding process, because that would negate the whole reason for Echochrome’s existence.

By the way, if you hold [R1] while rotating the camera, said camera moves much more quickly. This is particularly useful when you’re scrambling to reposition the structure ‘beneath’ a tumbling mannequin, which has just fallen through a misaligned black hole and is now floating in the game’s white abyss of a background (or is it a foreground?).

Some of the most complex levels in Echochrome are mindbenders, but the components used in their construction remain the same from beginning to end. Black holes can be used to drop your mannequin to a level that looks to be directly ‘below’ its present situation. Then there are white jump points, which ping your mannequin into the ether. Apparently the perspective taken as your character walks onto the jump point dictates its flight path. Indeed, this is one of the few needlessly frustrating aspects of Echochrome, as the direction of jumps can seem almost random. Often the only solution is to conduct a trial-error experiment, lining up the camera at a number of different angles before luckily discovering a perspective that lets you jump to the desired destination.

It’s a bit of a pain in the cranium. I still managed to forgive and forget this gripe (although I’m bringing it up again now like a filthy hypocrite), and it doesn’t exactly undermine the whole game. It’s just a frustration that the player doesn’t deserve, in a game where there are plenty of legitimate frustrations in the shape of brainteasing level design. These frustrations are the good ones, the ones that turn Echochrome into a surprisingly addicting game.

Echochrome clicks nicely because its central concept is a self-perpetuating chase, where you need to guide Mr (or Ms) Mannequin through/along/up to/down to/between/behind some twisted structures until it meets up with its own shadow - shadows, sorry. There are a few of them, and they’re dotted around each level so that you need to explore the whole place before being able to segue into the next level.

So, this is how it works, clever clogs: you’ve got a little mannequin character that never stops walking unless you press [Triangle] to freeze the action and work out a solution to the stage. All this walking doesn’t get it very far by default, because it’s treading a path along the surfaces of impossible structures. That’s where you come in – you need to change your perspective of the structure, either by pushing an analogue stick or waving the SixAxis like, well, like a Wii Remote.

The control system couldn’t be simpler, but the level design is deliberately convoluted and all the better for it. I was stuck on the third level for half an hour. No shame in that, though, because Echochrome is more difficult than a cryptic Times crossword. One look at our Echochrome screenshots will tell you that it owes a huge debt to M.C. Escher and his mad geometry, but it’s not just something to leave running on your plasma display when it’s not being used... Echochrome is more than art: it’s a game. Ha!

There are a few nifty subtleties to the control setup, which seem to have been included just to smooth everything over. Pressing the [Square] button ‘snaps’ your current perspective to automatically link any linkable edges of structures; but only if you’ve already brought those edges reasonably close to an alignment. This is just a neat way of sidestepping the need for gentle-gentle perspective shifts; it doesn’t fully automate the path-finding process, because that would negate the whole reason for Echochrome’s existence.

By the way, if you hold [R1] while rotating the camera, said camera moves much more quickly. This is particularly useful when you’re scrambling to reposition the structure ‘beneath’ a tumbling mannequin, which has just fallen through a misaligned black hole and is now floating in the game’s white abyss of a background (or is it a foreground?).

Some of the most complex levels in Echochrome are mindbenders, but the components used in their construction remain the same from beginning to end. Black holes can be used to drop your mannequin to a level that looks to be directly ‘below’ its present situation. Then there are white jump points, which ping your mannequin into the ether. Apparently the perspective taken as your character walks onto the jump point dictates its flight path. Indeed, this is one of the few needlessly frustrating aspects of Echochrome, as the direction of jumps can seem almost random. Often the only solution is to conduct a trial-error experiment, lining up the camera at a number of different angles before luckily discovering a perspective that lets you jump to the desired destination.

It’s a bit of a pain in the cranium. I still managed to forgive and forget this gripe (although I’m bringing it up again now like a filthy hypocrite), and it doesn’t exactly undermine the whole game. It’s just a frustration that the player doesn’t deserve, in a game where there are plenty of legitimate frustrations in the shape of brainteasing level design. These frustrations are the good ones, the ones that turn Echochrome into a surprisingly addicting game.

Echochrome clicks nicely because its central concept is a self-perpetuating chase, where you need to guide Mr (or Ms) Mannequin through/along/up to/down to/between/behind some twisted structures until it meets up with its own shadow - shadows, sorry. There are a few of them, and they’re dotted around each level so that you need to explore the whole place before being able to segue into the next level.

Games:

echochrome

Read More Like This

Comments

iv downloaded the demo for ps3 and psp an love it can not wait for the full game to come out in uk i feel its a bit like portals which i also love

Bah, blatant ripoff of "Mike Edwards' Realm of Impossibility", heh...

more comments below our sponsor's message

Of all the games in production right now, including the new Street Fighter, this is the one I'm most looking forward to. The concept is just delicious, even if it's not entirely new, it's going to take it a million miles further than in the past.

Oh, I was at least 33/64ths joking...if anything I'd see it as an homage...I hope its credited...one of the old "albums", Pokemon might as well be Mail Order Monsters, I'm still waiting for Racing Destruction Set Redux, though if EA could see fit to loan me a studio (surely they've got one spare) for a while I'll do it myself...then, and only then will I feel the opression of XBLs content policies...might even be enough to get a PS3, but only if I can get someone to mod a DualShock3 into a 360 'troller shell...my sticks are asymetrical now baybee, I ain't never goin' back! Plus, those sorry excuses for triggers are, "...like convex, man...", he said, his voice dripping the contempt of the counterculture, pronouncing convex so that it rhymed with "square", and drawing in the air a lumious rectangle which hung there mockingly until it faded from view...

edit:no, wait they could do a file share thing for teh tracks...no furries...

edit:no, wait they could do a file share thing for teh tracks...no furries...

PreciousRoi wrote:

Oh, I was at least 33/64ths joking...if anything I'd see it as an homage...I hope its credited...one of the old "albums", Pokemon might as well be Mail Order Monsters, I'm still waiting for Racing Destruction Set Redux, though if EA could see fit to loan me a studio (surely they've got one spare) for a while I'll do it myself...then, and only then will I feel the opression of XBLs content policies...might even be enough to get a PS3, but only if I can get someone to mod a DualShock3 into a 360 'troller shell...my sticks are asymetrical now baybee, I ain't never goin' back! Plus, those sorry excuses for triggers are, "...like convex, man...", he said, his voice dripping the contempt of the counterculture, pronouncing convex so that it rhymed with "square", and drawing in the air a lumious rectangle which hung there mockingly until it faded from view...

edit:no, wait they could do a file share thing for teh tracks...no furries...

edit:no, wait they could do a file share thing for teh tracks...no furries...

Well, MGS4, GT5 and GOW3 all say hi. And it's doubtful about echochrome crediting anything, there's no reason to. Let me tell you a story about little parasitic aliens that latch onto a person and turn them into a psycotic mutant type weirdos. you may be thinking of 'the flood' from halo right now but the original concept was actually from half-life. you remember that right, the critically acclaimed game? WAIT WHAT'S THIS!? master chief has a suit with shielding as well!? THAT ACTUALLY MANAGE TO INVADE EARTH!!!?? and you have to what? HELP TO LIBERATE EARTH FROM THEIR INVASION!? man, so much stuff from the halo series has been robbed from half-life in an attempt to make the ''ultimate fps'', i don't see any credit anywhere.

Unless you know what Realms of Impossibility is, and why its relevant, kindly STFU

k, thx.

k, thx.

meh, he prolly won't take it...the moron actually thinks parasitic, mind-controlling, Earth-invading aliens were an "original" idea from Half-Life that Halo "stole"...blithely ignored my statement that I was more than half-joking and used it as an excuse for an anti-Halo, pro-PS3 (though I'm not sure why he thought the upcoming exclusives are relevant to the discussion) rant.

...as for giving credit where its due, there most certainly is a need, bleatings about what someone else did, or you think they did machts nicht. Delving into parts of the interweb I rarely frequent (gaming sites that aren't SPOnG), I find I'm not the first or the only person to see Echochrome and think Realm of Impossibility. But then I think I knew thats what I'd find, a platformer based on Escheresque geometry is pretty distinctive.

...as for giving credit where its due, there most certainly is a need, bleatings about what someone else did, or you think they did machts nicht. Delving into parts of the interweb I rarely frequent (gaming sites that aren't SPOnG), I find I'm not the first or the only person to see Echochrome and think Realm of Impossibility. But then I think I knew thats what I'd find, a platformer based on Escheresque geometry is pretty distinctive.